How serious is the P800 Yakhont threat? Does it have a destabilizing effect on the Middle East?

Posted by Tamir Eshel

The

launch vehicle unit carrying two Yakhont anti-ship missiles in

container launchers. The missiles are carried in the recessed position

and launched vertically from the erected canisters.

AEGIS systems, used on U.S. Navy and many NATO vessels, the European PAAMS, used by the Royal Navy, French and Italian navies and Israel’s new Barak 8 ship air defense system are designed to match such treats. So does Israel’s ‘Magic Wand’ system, employing the Stunner missile interceptor, capable to counter these potent missiles effectively if employed in surface/surface or ship/surface role. However, the majority of smaller naval vessels, still equipped with ‘point defense’ anti-missile systems were not designed to counter such high speed attacks, particularly when it comes in salvos of two or four missile.

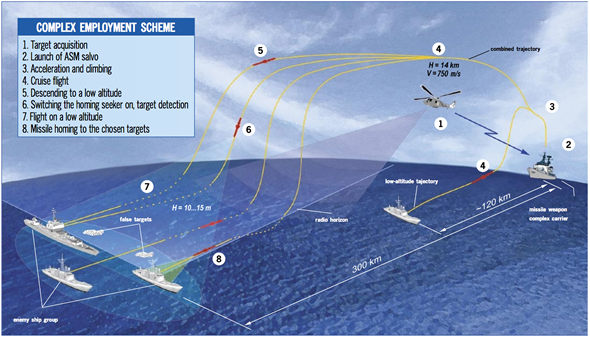

Such elements are at risk within ranges of 300 km, by missiles fired from the Mediterranean Syrian naval bases at Tartus and Latakia. Yakhont typically cruises to the target area at high altitude, and then descends for a sea skimming attack from under the horizon. The distance at which it begins its descent can be programmed before launch, by determining the achievable range, which is between 120 (low level flight) – 300 km (high mid-course, low-level beyond the horizon to the target.

The

potential coverage of P800 Yakhont missiles fired from coastal sites

(Tartus) or land sites in Southern Syria cover Israel's Mediterranean

Naval Bases.

The

operational concept of the Bastion P coastal defense system employs

multiple mobile launchers each carrying two Yakhont missiles, capable of

attacking targets at a distance of 250 km from the coast. Targeting is

provided by helicopters or other airborne platforms, coastal radars or

ships at sea. Each launch unit is operating independently, or coordinate

its activity with another launch vehicle located up to 15 km away,

targeting, command and control are provided by the central command

vehicle and regional command post that can be located more than 25 km

apart.

If the Syrians are seriously planning to extend their operational reach with the missile, one has to watch out for Syria to reach for UAVs, naval patrol aircraft (Be-200 or Il-38 from any CIS nation or other countries (decommissioning such aircraft could be an option). Such transfer of equipment could be unnoticed as it does not involves weapons transfer. They could also opt for upgrading the Su-24MK ‘Fencer D’ to take on maritime recce role. Even more serious is a combination of Su-27/Su-30 and P800s, which could provides the P800 with the stand-off targeting and attack capability against surface targets. The Russians are using their Onyx version of the weapon with their Su-33 carrier-based naval fighters. By knowing the P800 is within range, the Israeli Navy will definitely lose its dominant and unchallenged position in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly along the Lebanese coast, and therefore should take defensive measures – certainly be on guard, which it failed, during the Second Lebanon War in 2006, when ISN Hanit was hit unexpectedly by a Hizbollan C-802 missile – having turned off its on-board defensive systems.

Of course, for deliberate ‘ambush’ attacks Syria could try deploying forward targeting using merchant or fishery vessels sailing in the Eastern Mediterranean or submarines, provided by allies such as Iran (since Syria do not have any submarines now, after decommissioning their 3 Romeo subs about six years ago). But this is really a long, long shot that would cost Syria dearly.

Altogether, for the short term, the arrival of the P800 in the Mediterranean is a serious threat. Over time, as the Israel Navy gets its Barak-8 missiles and ‘Magic Wand’ deployed, the threat could be contained, given the Syrians will not deploy large numbers of these missiles on platforms and constellations that would maximize its capability to launch saturation attack against the IN leading vessels. Whatever the case may be, both sides, the Syrians and the Israelis need time to deploy and defend so the threat may be serious, at first sight, but viable solutions are already in sight.

The Russians are using their Onyx version of the weapon with their Su-33 carrier-based naval fighters.

Based on the content of this article, you might be interested in the following posts

No comments:

Post a Comment