By Andrew KORYBKO (USA)

Oriental review

Oriental review

(Please read Part I prior to this article)

(Please read Part I prior to this article)

The Power Of The Christian Community

The State Of Religious Affairs:

What’s usually left out of the conversation when discussing Albania

is the strategic Christian minority inhabiting the northern and southern

border regions, and the potential for them to sympathize more with

their co-confessionalists next door than with their “Greater Albania”

ethnic counterparts in Tirana. It’s no secret that Christian influence

is on the upswing in the Balkans, and this zeitgeist has even spread

into Albania in the years since communism. Although recognized as a

majority-Muslim state, the

2011 census

surprisingly lists 10% of the population as being Catholic and 6.7%

being Orthodox, with each denomination being clustered in the north and

south of the country, respectively.

In total, this makes for a population that’s 16.7% Christian as

compared to 58.7% who are Muslim, but there’s an important qualitative

difference between the two, and it’s that the Christians are much more

pious than the largely secular Muslims. After all, it wasn’t just for

show that Pope Francis chose Albania to be his

first European trip outside of Italy

in September 2014, and scattered online reports indicate that Muslim

conversions to Christianity (specifically Catholicism and its related

sects) are on the rise. Concerning the Albanians that occupy Kosovo,

Reuters even ran a 2008

piece

detailing how some of them have decided to embrace their

“crypto-Catholic” roots, which underscores the developing role that

Christianity is playing in the Albanian-populated areas of the Balkans.

Catholicism On The Come Up:

An

Ethnic Albanian couple carrying a portrait of Mother Teresa draped with

Albanian Flag, as they attend a Mass in Pristina, Kosovo

One can also recall at this time the global renown of the late

Catholic nun popularly known as Mother Teresa, an ethnic Albanian

originally from the territory of the Republic of Macedonia (Skopje, to

be exact). Her beautification by the Catholic Church has placed her on

the short list to sainthood, and she remains one of the most well-known

Albanians to this day. Because of her Albanian ethnicity and the warm

feelings most of the world has towards her, she’s become a symbol of

sorts for the country and is even quite popular within it. There has yet

to be any quantitative evidence produced to establish the following,

but it could be that the “Teresa Effect” has made some non-religious or

even Muslim Albanians more receptive to Christianity, similar to how the

so-called “Francis Effect” has invigorated many lay Catholics.

Of course, it goes without saying that the Vatican has its own

self-serving interests in proselytizing the faith across the Strait of

Otranto, but it’s undeniable that Christianity (most specifically of the

Catholic denomination) has become a tangible fact of life in some parts

of Albanian society nowadays. The author is personally impartial to

this process and doesn’t want to come off as supporting any religion or

denomination over the other, but it needs to be objectively recognized

by the reader that Albania is, however surprising it may sound to some,

one of the few places in the world where Christianity has grown since

the end of the Cold War.

Switching Places:

As a self-assertive and proselytizing Christianity comes up against a

secular and stagnant Islam, there are bound to be political

consequences in the near future, especially as some representatives of

the dominant faith become more conservative in reaction to the upstart

religion. This is peculiarly ironic, since it mirrors exactly what’s

happening in the EU, except with the roles of Islam and Christianity

reversed. Just as there are some Christian-affiliated extremist groups

that agitate for violence against Muslims, so too will there likely be

Islamist-affiliated ones that target Christians. Neither of these

faith-based radicals represents the bulk of their co-confessionals, but

nonetheless, they’re the loudest, most visible, and most violent

reactionaries from a largely passive majority.

In the EU case, many fret that there are foreign influences guiding

the large-scale insertion of Islamic elements into their traditionally

Christian societies, and a similar fear could predictably be felt in

Albania as per the Catholic proselytizers (“missionaries”) operating in

the mostly Muslim country. In both cases, it’s understandable that

there’d be a domestic backlash of sorts by the host representatives

against the “new arrivals”, even if they’re really native converts such

as the Christians in Albania. It’s guaranteed that inter-communal

tensions would skyrocket the moment any of these minority identity

groups begin engaging in politics or pushing an agenda that is perceived

(keyword) to be affiliated with their religion. The author doesn’t

intend to justify any sort of violence between these groups, but rather

hopes that the previous explanation can help the reader understand the

process that is already taking place in Europe, and might soon develop

in Albania if the structural similarities between the two’s relationship

to upstart religions are any reliable indication.

Vanguard Dissidents:

Vanguard Dissidents:

The Christian minority in Albania is strategically positioned to

become the vanguard dissidents against the Tirana elite’s ‘unifying’

ideology of “Greater Albania”. Like was mentioned at the beginning of

Part II, the Albanian power-makers fear that this demographic might come

to identify more with its co-confessionalists next door than with their

ethnic counterparts in the capital, and that the first form of

resistance this may take is in objecting to “Greater Albania”. They

might have their practical and pragmatic reasons for this, such as not

wanting to create another failed region in the Balkans like Kosovo, or

it might be motivated by barely concealed religious concerns that

“Greater Albania” is really a code word for anti-Christianity, again, as

seen by the example of Kosovo. No matter what drives them to do so, the

moment this demographic starts pushing back against “Greater Albania”,

that’s when the country will begin entering the most serious crisis in

its history, conceivably one which may reach existential proportions.

To explain, no other identity group in Albania is capable of

coalescing into a unified bloc quicker than the Christians (and

especially Catholics) are, and if they can mobilize any of their

existing or soon-to-be-created civil society organizations to help

advance a political goal, then they’d immediately emerge as a major

force to be reckoned with in Albanian society. Neither Ghegs, Tosks, nor

Muslims have as much potential in currently doing so as Christians

because the self-awareness of their distinct identities has yet to set

in, largely due to the distracting success of “Greater Albania”.

Therefore, if the group least affected by this ideology turns into the

first one to publicly oppose it (on whatever grounds, be they pragmatic,

religious, or a hybrid of both), then it would prompt the government to

react in some form or another in order to save the ‘unifying’ ideology

that it so desperately needs in order to remain in power and keep

“Albanians” from decentralizing into mores specific Gheg, Tosk, and

Muslim identities.

The Islamic Backlash

The First Move:

There are many ways in which Tirana could respond to the Christians’

resistance to “Greater Albania”, but the shape it takes ultimately

depends on what the dissidents do first. Although it’s possible to

project some type of protests in the event that “Greater Albanian”

rhetoric once more hits dangerous proportions in Tirana, it’s more

likely that such resistance will first be passive and will refrain from

physical manifestations until that point. To expand on this idea, it’s

probable that local civic figures and Christian-identifying politicians

could try to raise the issue whenever given the chance, preferably in a

mass media or grassroots (canvassing) platform, despite the reputational

and/or career repercussions this could have. The emergence of Christian

individuals agitating against “Greater Albania” will be seen by

decision makers as being religiously motivated and influenced from

abroad (even if this isn’t the case and such actions are driven purely

by domestic pragmatism), so they’d probably reactively resort towards

encouraging the soft Islamization of society, which might even include

enhanced cooperation with Turkish government-affiliated organizations in

a hasty effort to emulate part of Erdogan’s ‘success’.

The Turkish Connection:

President

of Albania, Bujar Nishani and President of Turkey, Recep Tayyp Erdogan

attend the foundation stone ceremony on Mosque of Namazgja site in

Tirana, May 2015.

At this point it doesn’t matter if the Prime Minister is Christian

(like Edi Rami), Muslim, or Atheist – what’s critical to understand is

that he and his elite cohorts have a high likelihood of responding to

any Christian-affiliated dissent (even if not religiously motivated) by

mechanically trying to ‘unify’ the population under the alternative

ideology of Islamism (wrongfully assuming that this would succeed simply

because a majority of the population is Muslim), following in the

footsteps of their national ‘big brother’ in Turkey. It’s not

coincidental that Albania has allowed Turkey to begin building the

Balkans’ largest mosque

in its capital, personally inaugurated by the strongman himself during

his last visit to Tirana, since it’s a clear sign of the country’s

strategic submission to its historical occupant.

Erdogan might already be entertaining plans to shift his failed

Neo-Ottomanism away from the Mideast and towards the Balkans, and an

Islamified Albanian society along the Muslim Brotherhood tradition of

his preference would be seen as a red-carpet rollout for Turkey’s return

to the region. Thus, Erdogan indisputably has a strategic stake in

seeing his Albanian proxy following Turkey’s lead in Islamifying its

society, and if there’s even the tiniest opportunity for him to convince

his underlings in Tirana to go through with his preplanned vision for

their country out of what he would characterize as their ‘national

interest’ and/or ‘religious duty’, then he’ll surely seize It and supply

all manner of support as necessary.

“Mission Creep”:

Some of Albania’s decision makers might rightfully feel uncomfortable

about violating their country’s secularist traditions, but they’d

probably be ‘assured’ that such steps are going to be incremental,

‘comfortable’, and nothing too extreme from the existing standard.

Turkish strategists might even try convincing them that Islamization and

“Greater Albania” could actually become complementary ideologies, with

the former being ‘necessary’ in order to isolate the Christian

dissidents so that the latter can ultimately be achieved. This line of

thinking could come off as enticing and ‘manageable’ to the elite, who

might agree that a ‘back-up’ ideology is necessary to embolden the

Albanian base and discredit Christian naysayers.

As the Islamization of secular states historically shows, however,

this could quickly become an uncontrollable process that swiftly eludes

the management of the forces that initially set it into motion. When the

time comes that an Islamifying government finds itself under the

influence of the non-state actors that it had earlier set loose upon the

secular majority (and this always happens sooner or later in such

societies), then the threshold has irreversibly been passed to where

religious-affiliated terrorism can endemically take root in the country,

to say nothing of the assumed-to-be earlier advances of foreign-based

terrorist infiltrators (be they in ‘hard’ militant form or disguised via

‘soft’ Wahhabist clerics). One mustn’t forget the tens of thousands of

mostly Islamist-sympathizing Mideast migrants that Albania wants to

bring into the country in the near future either, since it’s sure that

they’ll have play an instrumental role in this process as well (and all

to Erdogan’s nodding approval).

Assessing The Destabilization Potential Of Albania

Situational Review:

“Greater Albania” has consistently been pursued in one form or

another as the country’s de-facto national ideology since the end of

communism, and there has yet to be a moment when significant domestic

dissent openly challenged the notions of this ‘unifying’ precept. It

should be recalled that there are two parallel processes ongoing in

Albanian society at the moment, with one being its Christianization and

the other its inevitable return to the full-scale promotion “Greater

Albania”. The reader would do well to remember that the latter is being

evoked as a distracting response to the large-scale economic crisis in

the country, following the pattern set out in 1997 in reacting to

similar (albeit more political) domestic difficulties during that time.

The “Greater Albania” trend will not turn against the country’s

Christian population (although it didn’t spare any of Serbia’s during

the Occupation of Kosovo), but Albanian Christians might turn against

“Greater Albania” for whatever their religious or pragmatic reasons may

be. This in turn would prompt a reaction from the authorities that is

predicted to unintentionally open the Pandora’s Box of identity

decentralization in Albania, with three scenario paths being the most

foreseeable.

People’s Revolution:

This scenario is the least ‘sexy’ of the three, but is the one with

the greatest chance of occurring. Once the ideology of “Greater Albania”

is challenged from within and its hypnotizing effect on distracting the

disaffected and impoverished majority of the country’s citizens has

faded, they may snap out of their earlier induced ‘trance’ and begin

attributing their plight to the elite that are truly responsible for it.

The chain reaction of social activism that this would set off could

turn Albania into the next “Moldova”, in the sense of civil society

organizing against its corrupt overseers and attempting to finally free

the country from their thieving clutches. A lot of this would be based

in the naiveté that they’d be able to make a pronounced difference by

enacting the symbolic retirement of one or two figureheads, but still,

in the context of this article, it would satisfy the criteria for

creating national destabilization, especially if the targeted leader

refuses to steps down, or even worse, resorts to state or militia

violence to disperse the protesters.

The difference between this scenario and a Color Revolution is that

this examined situation is entirely natural and free from external

tinkering. No foreign power manipulated Albania into creating the

deplorable conditions that gave rise to tens of thousands of its

citizens leaving their country and the colony of Kosovo this year alone,

since nobody is to blame for this but the Tirana elite themselves.

Additionally, it’s absurd to even conceive of a foreign power having a

hand behind the protests, since the US and the West would be dead-set

against them, while Serbia and Russia, aside from not having the

operational experience in handling such covert operations, have no

social capital whatsoever from which to recruit and influence Albanians.

This possible People’s Revolution would be entirely by Albanians and

for Albanians, and depending on the composition of its protesting

elements, it might even take on an extreme nationalist angle similar to

EuroMaidan (minus the foreign support in this case, it must once again

be reminded). That course of developments would all depend on how the

Tirana elite respond to the protest movement and exactly which social

elements play the leading parts in organizing it.

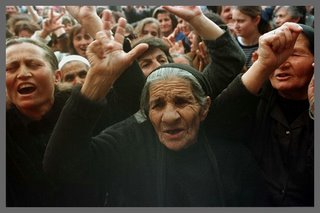

Religious Warfare:

Albania has a history of waging religious conflicts both without and

beyond its borders. During the leadership of Enver Hoxha, the state

implemented a lethal atheization policy where religious practitioners of

all faiths could be killed for their beliefs. This was an internal war

within the state between the government and all religions. After

communism ended, Albanian elements waged another religious war, also

with government support, but this time outside of its borders and with

the intent of brutally cleansing the Christian population out of Kosovo.

The time seems to be coming for a new stage to Albania’s religious

wars, and this time it might once again be concentrated within the

country itself.

The uptick in Christianity, especially if it’s politicized to an

extent, could lead to the ‘moderate’ state-sponsored Islamization of

society under Erdogan’s supervision. It might ‘logically’ begin as a

Turkish-advised reaction to any Christian dissent against “Greater

Albania”, but it could quickly spiral out of control and turn into a

bloody sectarian conflict that would inevitably involve the support of

foreign actors on both sides (perhaps morphing into a Serbian-Turkish

proxy war that takes on the misleading simplification of being Christian

vs. Muslim). Amidst the violence (or at the very least, inter-communal

tension), ISIL and other affiliated radical Wahhabist groups might find

fertile ground for gathering recruits and setting up base in the

increasingly fractured society, which would in any case bode extremely

negatively for the entire Balkan region at large.

The Fight For Federalization:

Catalyzed by the Christians’ awareness of their particular

sub-Albanian identity (no matter to what degree they express it, so long

as they do), the Ghegs and Tosks might become emboldened enough to

realize their own identity uniqueness, especially if society begins

Islamifying per the abovementioned scenario and individuals begin

searching for a ‘third way’. Understanding that the ‘unifying’ utility

of “Greater Albania” might be irreparably damaged once one sub-national

identity (predicted to be Christians in this case) begins expressing its

distinctiveness, it’s safe to assume that a ‘race for identities’ would

surely follow, and in this case, geo-dialect affiliation could possibly

become the most popular. In this projected reality, it’s conceivable

that the Gheg and Tosk spaces would make an effort to consolidate within

their zones so as to protect their identities from the ‘security

dilemma’ between one another, and between themselves and the religiously

connected ones that have just begun sprouting up (and precipitated this

whole identity crisis in the first place).

One of the most logical steps in this case would be for the Ghegs and

Tosks (predicted to be the two most dominant of the competing

identities) to formally delineate their spheres of geographic influence,

which as was written in Part I, would traditionally be along the

Shkumbin River. Having observed how state decentralization quickly

spirals out of control in the absence of a unifying ideology to keep

everything together, the only alternative to anarchy would be either a

military operation launched by the centralized authorities or the

federalization of the country along the lines of its most prominent

politically represented constituent parties. In the case of Albania,

it’s impossible at this point to predict if military force would be used

in such a scenario (and whether the military could remain united among

escalating identity tensions between its members), but it’s much more

plausible to assume that federalization between the quickly consolidated

Gheg and Tosk entities could seriously be discussed. In fact, depending

on the organization of the Christian community prior to the outbreak of

identity decentralization, they might even be able to attain a

semi-autonomous status either within Albania proper or inside one or

both of the two predicted federal entities (if it comes to it, most

likely in the Catholic portion of North Gheg).

Concluding Thoughts

Albanian politicians agitate for the Fascist-era recreation of

“Greater Albania” as a desperate measure to compensate for internal

weakness. The country’s failing economy precipitates the need to

distract the citizenry from internal woes, and the potential for a

North-South regionalist identity forming among the Gheg and Tosk dialect

communities compels the elite to continuously pursue this ‘unifying’

ideology. Largely neglected when discussing Albania but no less

important than its economic woes and geo-dialect division is the

emerging Christian community in the country, and it’s possible that this

new domestic identity might be self-assertive enough to set off a chain

reaction of identity decentralization in the future. If the Christians

mobilize into a semi-unified movement or union of interest groups and

begin pursuing a shared political cause, then they’d draw attention to

the presence of sub-national identities (desperately impoverished

citizens, Gheg speakers, and Tosk speakers) that the ‘unifying’ ideology

of “Greater Albania” tries to soothe over.

Should the Christians begin directly campaigning against “Greater

Albania”, be it through religious or pragmatic considerations, then that

would be the greatest (unwitting) attack on national unity that Albania

has ever experienced before in its history, and it would automatically

result in some sort of state-sponsored response. The predicted

Turkish-advised ‘soft’ Islamization of society, already apparently in

the cards for a future deployment, would ultimately end up being

disastrous for the unified state and would do more to polarize the

country than save it, despite Erdogan’s predicted assurances to the

contrary. In the ensuring tumult that’s sure to follow any revival of

sub-national identity consciousness in Albania (whether or not the

Islamist scenario comes into play), it can be heavily predicted that the

Ghegs and Tosks will start forming more distinct geo-dialect identities

that could pave the way for a weakening of the previously assumed

‘cohesive’ nature of the Albanian state. That by itself would probably

kill the national mobilization of support necessary to revive the vague

concept of “Greater Albania” once its citizens start thinking in terms

of “Gheg-Albania” and “Tosk-Albania” (if not outright Gheg and Tosk

identities outside the constructed Albanian nationality), and might

perchance become the most long-lasting (and ironically self-imposed)

deterrent to Albanian aggression, and consequently the most solid

guarantor of Balkan peace for the coming future.

Andrew Korybko is the American political commentaror currently working for the Sputnik agency, exclusively for ORIENTAL REVIEW.