The number of Muslims has burgeoned in this Italian city, but plans to build a mosque have been contentious.

Bologna, Italy - On

any given Friday on the outskirts of Bologna, where the tight porticoed

streets give way to the lazy sway of golden wheat fields, you will see

hundreds of Muslims making their way down what could be mistaken for a

country road.

They converge on an old warehouse, which has been converted into the Islamic Cultural Centre of Bologna, the city's largest mosque.

On a recent Friday during the holy Islamic month of Ramadan, over 100 worshippers were on the gravel outside, the building being full.

"We used to be tens praying at our centre," said Mohamed Redwan

Altounji, president of the cultural centre. "Now we are thousands."

Altounji arrived in Italy from Syria as a medical student 49 years ago. He is now 71 years old.

Bologna, nicknamed "The Red", is known for its university - the oldest in Europe - and its history of leftist politics.

From 2007 to 2009, it was the centre of a slowly unravelling political drama around plans to construct a mosque.

At one point in 2007, Roberto Calderoli of the far-right Lega Nord party, at the time vice president of the Italian Senate, called for a "Pig Day" during which opponents of the mosque would walk with pigs over the proposed site in an attempt to desanctify it.

"Because Bologna doesn't have much of a history of right-wing politics, city officials agreed to the project and never expected the opposition that followed," said Dino Cocchianella, director of Bologna's Institute for Social Inclusion, a branch of the local government.

A coalition of Lega supporters, Catholic clergy, and civil society groups organised against the mosque.

"Our office promotes a model of integration based on inclusion," explained Cocchianella.

"This means each community learns from each other and is enriched by the other - as opposed to assimilation which says, I accept you if you become like me," Cocchianella said.

"I'm afraid the majority of Bolognans right now are not open to the inclusion model. There is a fear of immigration, a sense of being invaded," Cocchianella said.

According to city statistics, the percentage of Bolognans with foreign citizenship have tripled since 2002, to 15 percent of the population.

The city had given a building permit for a piece of property purchased by the Islamic Cultural Centre.

But it began to backtrack in the face of opposition.

There were rumours that the mosque would be a mega-mosque with the tallest minaret in Europe, and that the centre was affiliated with UCOII, a union of Italian Islamic centres. UCOII is not recognised by the Italian government and is variously described by mosque opponents as being close to either Saudi Arabia or the Muslim Brotherhood.

But, Altounji responded to the objections, saying they are "pure fantasy".

"I saw a woman interviewed on TV who said she'd heard we were building a minaret 35 metres tall. Where did she get such an idea? We proposed one, three or four metres tall," said Altounji.

Allegations that the mosque would be funded by Saudi money, are "an invention", Altounji stated.

"I swear to you, we have never received money or been in contact with any foreign country," he said.

The issue came to a head in 2008 when Virginio Merola, then a city councilman with the centre-left Democratic Party and now mayor, accused the city's contacts in the Muslim community of being "untrustworthy".

Frustrated and offended, the Islamic Cultural Centre cut off communication with the city for the next six years.

A fresh beginning

The atmosphere has not improved much since, especially with the current influx of refugees from Africa and the Middle East and the rise of the xenophobic Lega Nord as the pre-eminent party of the Italian right.

Lega leaders marked the death this month of Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, the former archbishop of Bologna, highlighting his views of Islam as a threat to Christian Europe.

Alan Fabbri, the Lega leader of the Emilia Romagna region, where Bologna is located, called on Catholic Italians not to "surrender to do-goodery", and to defend their Christian identity in the face of an Islamic invasion. Lega Nord did not respond to requests from Al Jazeera for an interview.

This sort of rhetoric prompted the Muslim community of Bologna to break its silence.

"I would see Islam attacked in the press and I thought, it can't be that there's no one to answer for us," explained Yassine Lafram, 29, a member of the directorate of the Islamic Cultural Centre and founder and coordinator of the Islamic Community of Bologna (CIB), a union of eight of Bologna's 13 mosques.

The inaugural press conference announcing the formation of CIB was held in the summer of 2014 at city hall, to stress the Muslim community's perception of itself as part of Bologna.

The first question from journalists was about building a mosque, but Lafram said this was not a priority.

"The goal now is to put a face on Islam in Bologna. We don't want the press to drive our agenda," he said. Since then Lafram, who was born in Morocco and has lived in Italy for 18 years, has participated in dozens of events around the city, including discussions on extremism and interreligious prayers.

Arman Tanna, 30, is CIB's coordinator in the Bangladeshi community, which accounts for six of Bologna's 13 mosques.

His mosque, the largest, can accommodate 250 worshippers and is on the second floor of a nondescript building under a bridge, above a bar that often hosts punk concerts.

"Right now, what we're missing is visibility for our community," Tanna said. "We have mosques, but they're invisible."

That said, he also stressed that the mission of CIB is community engagement, not mosque-building. "We want to be transparent to the outside community, because fear comes from ignorance," Tanna said.

A minaret in the sky?

Irene who asked that her surname not be used, is a 30-year-old religion teacher at an elementary school in Bologna and has organised visits to Lafram's mosque.

Nevertheless, the idea of minarets on Bologna's skyline or a call to prayer in its soundscape is unsettling to her.

Don Stefano Ottane, however, a Catholic priest who

started a bimonthly interreligious dialogue in 2001, said that he could

imagine a minaret in Bologna's skies in 10 years time.

"There are different opinions on the matter in the church," he added diplomatically. "The road to get there is through more interreligious prayer. That's how you move the church."

"I hope the issue is closed," said Cocchianella about any future move to build a mosque. "Both for Islam and for the city."

It is a safe bet that the Lega crowd will never be won over. But it's the Don Stefanos and the Irenes and the Dino Cocchianellas that the Muslim community hopes to work with.

"We want to arrive together with the community at the realisation that we, Bologna, need this as a city. Our need for a mosque has to become their perception of reality," Yassine said.

And for that, they see no need to hurry. After all, they are not going anywhere.

"We are Bolognans of Islamic faith. We are educating our community on both our duties and our rights. We are at home here, and we will endure."

They converge on an old warehouse, which has been converted into the Islamic Cultural Centre of Bologna, the city's largest mosque.

On a recent Friday during the holy Islamic month of Ramadan, over 100 worshippers were on the gravel outside, the building being full.

|

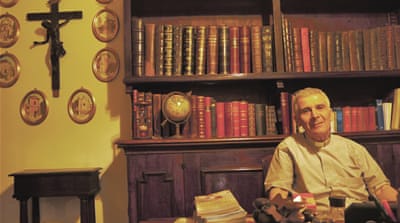

| Mohammed Redwan Altounj, president of the Islamic Cultural Centre in Bologna [Sean O'Neill/Al Jazeera] |

Altounji arrived in Italy from Syria as a medical student 49 years ago. He is now 71 years old.

Bologna, nicknamed "The Red", is known for its university - the oldest in Europe - and its history of leftist politics.

From 2007 to 2009, it was the centre of a slowly unravelling political drama around plans to construct a mosque.

At one point in 2007, Roberto Calderoli of the far-right Lega Nord party, at the time vice president of the Italian Senate, called for a "Pig Day" during which opponents of the mosque would walk with pigs over the proposed site in an attempt to desanctify it.

"Because Bologna doesn't have much of a history of right-wing politics, city officials agreed to the project and never expected the opposition that followed," said Dino Cocchianella, director of Bologna's Institute for Social Inclusion, a branch of the local government.

|

Our office promotes a model of integration based on inclusion. This

means each community learns from each other and is enriched by the other

- as opposed to assimilation which says, I accept you if you become

like me. |

"Our office promotes a model of integration based on inclusion," explained Cocchianella.

"This means each community learns from each other and is enriched by the other - as opposed to assimilation which says, I accept you if you become like me," Cocchianella said.

"I'm afraid the majority of Bolognans right now are not open to the inclusion model. There is a fear of immigration, a sense of being invaded," Cocchianella said.

According to city statistics, the percentage of Bolognans with foreign citizenship have tripled since 2002, to 15 percent of the population.

The city had given a building permit for a piece of property purchased by the Islamic Cultural Centre.

But it began to backtrack in the face of opposition.

There were rumours that the mosque would be a mega-mosque with the tallest minaret in Europe, and that the centre was affiliated with UCOII, a union of Italian Islamic centres. UCOII is not recognised by the Italian government and is variously described by mosque opponents as being close to either Saudi Arabia or the Muslim Brotherhood.

But, Altounji responded to the objections, saying they are "pure fantasy".

"I saw a woman interviewed on TV who said she'd heard we were building a minaret 35 metres tall. Where did she get such an idea? We proposed one, three or four metres tall," said Altounji.

Allegations that the mosque would be funded by Saudi money, are "an invention", Altounji stated.

"I swear to you, we have never received money or been in contact with any foreign country," he said.

The issue came to a head in 2008 when Virginio Merola, then a city councilman with the centre-left Democratic Party and now mayor, accused the city's contacts in the Muslim community of being "untrustworthy".

Frustrated and offended, the Islamic Cultural Centre cut off communication with the city for the next six years.

A fresh beginning

The atmosphere has not improved much since, especially with the current influx of refugees from Africa and the Middle East and the rise of the xenophobic Lega Nord as the pre-eminent party of the Italian right.

Lega leaders marked the death this month of Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, the former archbishop of Bologna, highlighting his views of Islam as a threat to Christian Europe.

Alan Fabbri, the Lega leader of the Emilia Romagna region, where Bologna is located, called on Catholic Italians not to "surrender to do-goodery", and to defend their Christian identity in the face of an Islamic invasion. Lega Nord did not respond to requests from Al Jazeera for an interview.

This sort of rhetoric prompted the Muslim community of Bologna to break its silence.

"I would see Islam attacked in the press and I thought, it can't be that there's no one to answer for us," explained Yassine Lafram, 29, a member of the directorate of the Islamic Cultural Centre and founder and coordinator of the Islamic Community of Bologna (CIB), a union of eight of Bologna's 13 mosques.

The inaugural press conference announcing the formation of CIB was held in the summer of 2014 at city hall, to stress the Muslim community's perception of itself as part of Bologna.

The first question from journalists was about building a mosque, but Lafram said this was not a priority.

"The goal now is to put a face on Islam in Bologna. We don't want the press to drive our agenda," he said. Since then Lafram, who was born in Morocco and has lived in Italy for 18 years, has participated in dozens of events around the city, including discussions on extremism and interreligious prayers.

Arman Tanna, 30, is CIB's coordinator in the Bangladeshi community, which accounts for six of Bologna's 13 mosques.

His mosque, the largest, can accommodate 250 worshippers and is on the second floor of a nondescript building under a bridge, above a bar that often hosts punk concerts.

"Right now, what we're missing is visibility for our community," Tanna said. "We have mosques, but they're invisible."

That said, he also stressed that the mission of CIB is community engagement, not mosque-building. "We want to be transparent to the outside community, because fear comes from ignorance," Tanna said.

A minaret in the sky?

Irene who asked that her surname not be used, is a 30-year-old religion teacher at an elementary school in Bologna and has organised visits to Lafram's mosque.

Nevertheless, the idea of minarets on Bologna's skyline or a call to prayer in its soundscape is unsettling to her.

|

| Don Stefano Ottane, Catholic priest [Sean O'Neill/Al Jazeera] |

"I

think it's an irrational fear that comes from the idea that the

presence of the 'Other' signifies the weakening of the familiar," she

explained.

"There are different opinions on the matter in the church," he added diplomatically. "The road to get there is through more interreligious prayer. That's how you move the church."

"I hope the issue is closed," said Cocchianella about any future move to build a mosque. "Both for Islam and for the city."

It is a safe bet that the Lega crowd will never be won over. But it's the Don Stefanos and the Irenes and the Dino Cocchianellas that the Muslim community hopes to work with.

"We want to arrive together with the community at the realisation that we, Bologna, need this as a city. Our need for a mosque has to become their perception of reality," Yassine said.

And for that, they see no need to hurry. After all, they are not going anywhere.

"We are Bolognans of Islamic faith. We are educating our community on both our duties and our rights. We are at home here, and we will endure."

Source: Al Jazeera

No comments:

Post a Comment